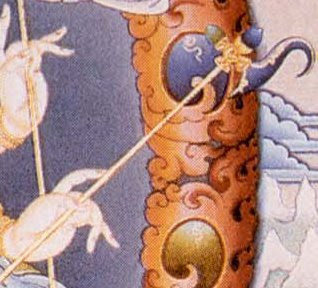

So, we arrive at this point with the idea that Mahakala begins with Avalokitesvara's compassionate vow to grant wishes, and that the practice of White Mahakala exists in an unbroken lineage direct from Avalokitesvara himself.The thing to do now is investigate why we are interested in this practice.Many people are interested in solutions to problems arising from perceived differences between intrinsic desires and extrinsic appearances in three areas: personal wealth, personal relationships, and personal health. For example: some who approach Tibetan Buddhism develop an interest in wealth deities such as Dzambala, magnetizing deities such as Kurukulle, or life-extending deities such as White Tara.

So, we arrive at this point with the idea that Mahakala begins with Avalokitesvara's compassionate vow to grant wishes, and that the practice of White Mahakala exists in an unbroken lineage direct from Avalokitesvara himself.The thing to do now is investigate why we are interested in this practice.Many people are interested in solutions to problems arising from perceived differences between intrinsic desires and extrinsic appearances in three areas: personal wealth, personal relationships, and personal health. For example: some who approach Tibetan Buddhism develop an interest in wealth deities such as Dzambala, magnetizing deities such as Kurukulle, or life-extending deities such as White Tara.

Such people candidly want money, love, and a long, healthy life, and they believe by cultivating this or that deity they will achieve their goals. For them, Buddhist practice becomes a type of sympathetic magic. Their prayers become desperate entreaties to beings they come to identify as gods. They believe that gods grant wishes if properly supplicated. They come to lamas in order to learn such proprieties and they acquire whatever supports they think are necessary.

I am not saying this is wrong, I am not saying this is right, I am not making any judgment about this at all. I am just saying this happens.

It is my personal belief that the loving kindness, generosity, and exquisite care extended by buddhas and bodhisattvas toward all sentient beings in the six realms are without any limitations or conditions whatsoever.

I do not think buddhas and bodhisattvas discriminate between beings based on who prays the loudest, or who has the most beautiful altar, or who gives the most elaborate offering.(*)

The prayers, altars, and offerings are expressions of our own kindness, generosity, and care. The deities of health, wealth, and influence personify the qualities that we, as Buddhists, have an absolute duty to first emulate and then, as we spiritually mature, ultimately embody.

The great beauty of Tibetan Buddhist practice is that it works. In the initial stages, we may come to these practices for entirely selfish motives. Ultimately, we will abandon the selfish component of our thoughts. This will happen naturally, after we wear ourselves out with our experiences.

Instead, we will take as our personal goal the happiness and welfare of all sentient beings. Then, as we perform the Sadhana of White Mahakala, our thoughts will be of others. When we ask Mahakala to assist us, it will only be to the extent necessary to enable our service to others. We will begin to appreciate what this practice really stands for, and any self-absorbed artificiality will dissolve of its own accord.

In many countries around the world, there are government lotteries. The winners receive great sums of money—sometimes tens of millions of dollars.

Naturally, such lotteries excite the desires and imaginations of many people. The conventional thinking is, “Oh, if only I could win, I would build beautiful temples for Buddha and help all the poor people.”

Most would consider this an altruistic motive, and they might pray to White Mahakala on this basis, entering a type of bargaining process with the deity, saying, “If you do this, I promise I will do that.”

Do I need to tell you it does not work this way? The genuinely altruistic act is to do whatever you can; right this minute, for the welfare of beings. The genuinely altruistic thought is, “May everyone receive their heart’s desire.” That is what we are really saying when we perform this practice.

When we ask for something for our companions, and ourselves, we are intending that the entire Sangha receive that which is necessary to actualize the assistance of all sentient beings.

We do this because we understand that poverty is one of the occasions of suffering, and we therefore wish to eliminate the cause of poverty. We understand that the causes of poverty are avaricious thinking, and miserliness, whereas the causes of surplus are altruistic thinking, and generosity. We therefore employ this practice to turn our minds away from greed and avarice toward moderation and munificence.

If you ever have the opportunity to travel in remote areas where people practice Tibetan Buddhism, you may find people who are quite poor by any standard. You can see this in parts of Siberia, Mongolia, and Tibet.

Yet, even in the most humble home—in a nomad’s ger, for example—you will find altar fittings of the finest silver and gold. Often, a family will save for many years in order to provide these, enduring personal sacrifices, and even hunger.

This is not because the deities demand silver and gold. This is not a matter of impressing guests. This is not because the practitioner expects something in return. Rather, this is a reflection of the practitioner’s inner relationship with the sacred. This is a measure of the practitioner’s inherent respect, and even generosity.

The practitioner is saying that her circumstances may be humble; nevertheless, she unconditionally dedicates the surplus riches she has managed to accumulate to all sentient beings. In one sense, she accomplishes this through the medium of the deity, who has powers greater than her own. She asks the deity to help her practice generosity in the very best manner.

although most of us enjoy great material comforts, it seems that we do not rise to the level of our seemingly less fortunate brothers and sisters.

In the developed nations, we often take a rather narrow view. For example: we see an image that costs $200, and another image of the same deity that costs $2,000, and we automatically begin a subliminal dialogue: “Why should I pay $2,000 just to make somebody else rich? That $200 image will do just as nicely.” We start bargaining again. We become caught in the numbers. We think we are saving money. However, we fail to understand that this sort of thinking leads to poverty.

all images are nirmanakaya. all images are equal. Price, and even workmanship, is utterly unimportant. What is important is our relationship to the sacred.

Our spiritual friends, such as our teachers, can introduce us to the sacred, but after that, maintaining the relationship becomes our responsibility.

We want to enlarge the space that the sacred occupies in our lives. We want to erase attachment and aversion. The task becomes simple: honestly doing the best we possibly can. Maintaining any sort of relationship takes effort. We cannot allow lazy mind to defeat our progress.

Sometimes we develop an angry, impatient relationship with our practice. Here we sit, repeating this or that mantra so many times. Why does it have to be ten times? Would not eight times do just as well? Why cannot we finish the whole thing right now, so we can go about our business?

If this happens to you, use it for your benefit. ask yourself what it is you would rather be doing, and why. Examine the source of your impatience. Examine the source, content, and object of your anger.

Why are you angry? What does this anger consist of? Where is this anger directed?

Examine all the times you have been angry and impatient in the past. Remember the outcome. ask yourself why this time the outcome might be any different.

When your hand clenches so tightly, learn how to effortlessly open your hand. Just drop whatever you are holding. This, too, is a form of generosity. You extend this generosity to yourself.

You must approach the practice of White Mahakala with an open hand, a generous spirit, and a liberal mind. These qualities must be firmly rooted in compassion. Compassion is what drives the entire practice. White Mahakala is in fact manifested from the heart of avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

If you are able to develop genuine compassion for others, and if you make this the foundation of your practice, then even if you cannot accomplish the visualizations or complete the mantras, your practice will bring results.

Please have confidence in this. The hours you spend in confident practice are the best hours of your life.

This is Part 2 of a 5 part series:

Part 1: http://tibetanaltar.blogspot.com/2009/07/white-mahakala-part-1.html

Part 2: http://tibetanaltar.blogspot.com/2009/07/white-mahakala-part-2-of-5.html

Part 3: http://tibetanaltar.blogspot.com/2009/07/white-mahakala-part-3-of-5.html

Part 4: http://tibetanaltar.blogspot.com/2009/07/white-mahakala-part-4-of-5.html

Part 5: http://tibetanaltar.blogspot.com/2009/07/white-mahakala-part-5-of-5.html

(continues with part 3)

--------------

(*) Before engaging in certain acts, some bodhisattvas consider the benefit to others, the status of beings, the number of beings, this and future lives, vows and non-virtue, the pros and cons of the various types of generosity, beings’ levels of devotion, and their own practice. Other bodhisattvas engage in spontaneously correct activity that is perfect in each situation.  Chinese 4th, M-T-K 4th. Pig, Khon, White 1. Chokhor Duchen. Today celebrates the first turning of the Wheel of the Dharma. The effects of positive (or negative) actions are multiplied by 10 million today.

Chinese 4th, M-T-K 4th. Pig, Khon, White 1. Chokhor Duchen. Today celebrates the first turning of the Wheel of the Dharma. The effects of positive (or negative) actions are multiplied by 10 million today. Published every day at 00:01 香港時間 but written in advance and auto-posted. See our Introduction to Daily Tibetan Astrology for background information. If you know the symbolic animal of your birth year, you can get information about your positive and negative days by clicking here. For specific information about the astrology of 2009, inclusive of elements, earth spirits, and so forth, please consult our extended discussion by clicking here. The baden senpo (bad days to raise prayer flags) this year are: July 2, 14, 28; August 10, 24; September 5, 19; October 1, 2, 13, 28; November 23; December 5, 20.

Published every day at 00:01 香港時間 but written in advance and auto-posted. See our Introduction to Daily Tibetan Astrology for background information. If you know the symbolic animal of your birth year, you can get information about your positive and negative days by clicking here. For specific information about the astrology of 2009, inclusive of elements, earth spirits, and so forth, please consult our extended discussion by clicking here. The baden senpo (bad days to raise prayer flags) this year are: July 2, 14, 28; August 10, 24; September 5, 19; October 1, 2, 13, 28; November 23; December 5, 20.